"Welcome to Mars!"

We visit a simulated Martian habitat that's helping NASA prepare humanity for its next giant leap

President Trump’s call for “American astronauts to plant the Stars and Stripes on the planet Mars” increased public interest in the continuing research and development of SpaceX’s Starship, a prototype of the rocket Elon Musk hopes will deliver humans to the Red Planet.

But beyond the engineering challenges are questions about human physiology and psychology that NASA hopes to answer with a simulated Martian habitat called CHAPEA, an acronym for Crew Health and Performance Exploration Analog.

The research involves sending four volunteers at a time to spend more than a year living and working in the 1,700 square foot 3D printed habitat. During that time, the crew members eat freeze-dried meals, grow some of their own vegetables, conduct simulated spacewalks, and deal with contingencies real Mars explorers might face.

Communications with the outside world are intentionally delayed to simulate the 12 to 22 minutes it takes for a radio transmission to travel one-way between Earth and Mars, depending on the distance between their current positions on their respective orbits around the Sun.

And CHAPEA missions are long. The first one ran from June 25, 2023 to July 6, 2024. And the second mission, scheduled to begin in October 2025, is expected to have a similar duration to reflect the likely amount of time real astronauts would spend living on the surface of Mars (not including travel time to and from the Red Planet).

“Current Mars plans might include something like a nine month transit, a year to year and a half on the Martian surface, and nine months back,” said Suzanne Bell, an organizational psychologist with NASA’s Behavioral Health and Performance Lab.

“Living and working in a small, isolated, and confined space with a crew can be psychologically and physically taxing. So, we mimic that long-term isolation,” she said.

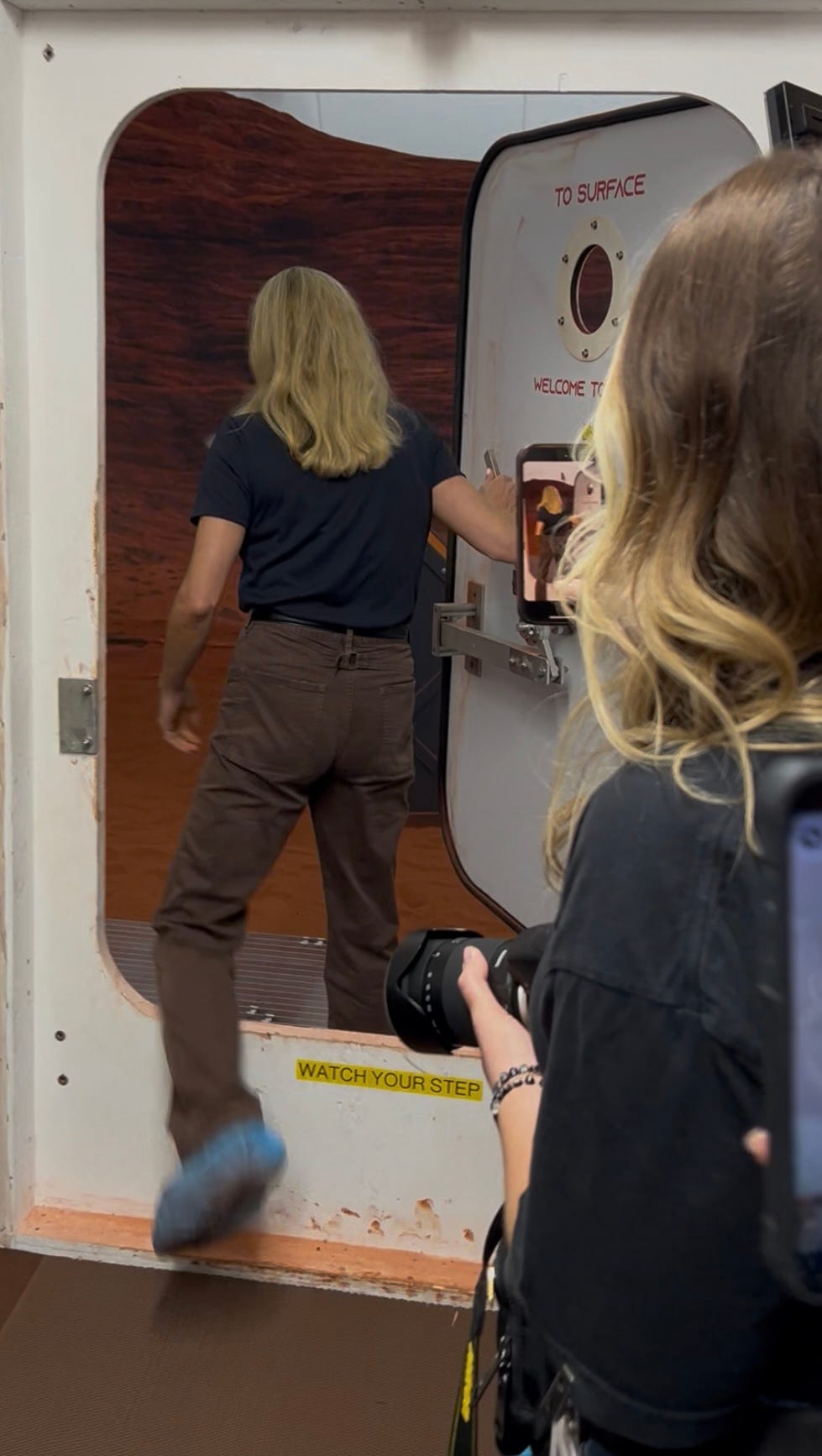

My colleagues and I enjoyed a considerably shorter and less challenging visit to the CHAPEA habitat, which is located inside a building at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

During our Mars walk, I donned a sport coat instead of a spacesuit. But we all wore plastic booties to avoid tracking foreign objects into the simulated Martian soil and to prevent our shoes from turning red.

The walls of the CHAPEA habitat have a similar reddish hue because an actual Mars outpost might be 3D printed using soil (regolith) from the Red Planet. This would eliminate the need to carry large amounts of construction supplies from Earth — a significantly more costly process.

With the need to keep payloads relatively small, Bell says what researchers learn from the human volunteers on CHAPEA simulations will help NASA determine which items are essential for astronauts to bring in order to survive and thrive on Mars.